In a decision that brings long-awaited clarity to to those dealing with Data Protection litigation in Ireland, the Supreme Court has ruled that emotional harm — including distress, anxiety, upset, and inconvenience — does not amount to a personal injury under the Personal Injuries Assessment Board Act 2003 (the PIAB Act) unless it constitutes a recognised psychiatric disorder.

The ruling in Dillon v Irish Life Assurance plc [2025] IESC 37 redefines the threshold between personal injury and non-injury claims and has significant procedural implications for data breach litigation, negligence claims, and cases seeking compensation for emotional harm. The judgment confirms that not all emotional damage attracts the legal protections afforded to personal injuries, and that IRB authorisation is not required for certain classes of claims.

Background to the Case: A Data Breach and a Procedural Dispute

Mr Patrick Dillon initially brought an action in the Circuit Court against Irish Life Assurance plc, claiming compensation for emotional harm after his private policy documentation was repeatedly sent to a third party in error — six times over a twelve-year period.

He alleged distress, anxiety, upset, and inconvenience arising from these data breaches, but did not claim to have suffered any physical or psychiatric injury, nor did he apply to PIAB for authorisation before issuing proceedings — a step usually required in personal injury cases under section 12 of the PIAB Act. The case was brought by Equity Civil Bill, rather than the Personal Injuries Summons format used in injury litigation.

The Circuit Court dismissed the claim as frivolous or bound to fail on the basis that it constituted an unauthorised personal injury action. The High Court upheld that dismissal. However, the Supreme Court granted leave to appeal, recognising that the issues raised were matters of public interest to those dealing with Data Protection litigation in Ireland.

To be – or not to be – a Personal Injury?

Delivering the unanimous decision, Murray J provided a detailed examination of both statutory and common law interpretations of “personal injury” in Irish law.

Emotional Distress Without Psychiatric Injury Is Not a Personal Injury

The Court held that claims for emotional distress alone — such as worry, stress, upset, or anxiety — do not constitute personal injuries within the meaning of the 2003 Act unless they are supported by evidence of a recognised psychiatric disorder.

This position is consistent with long-standing case law, including:

- Kelly v Hennessy [1995] 3 IR 253, where the Supreme Court required evidence of psychiatric illness to ground a claim in negligence;

- Fletcher v Commissioners for Public Works [2003] 1 IR 465, which reaffirmed that “grief or sorrow” without accompanying injury is not actionable; and

- Murray v Budds [2017] IESC 4, in which the Court confirmed there is no stand-alone right to damages for emotional upset alone.

Murray J rejected the lower courts’ finding that the distress Mr Dillon described fell within PIAB’s jurisdiction. The Court concluded that the 2003 Act was never intended to apply to non-clinical emotional harms, and requiring PIAB authorisation in such cases would misapply the legislation.

Two Distinct Legal Pathways for Privacy-Related Emotional Harm and Data Protection Litigation in Ireland

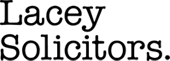

The judgment clarified that claimants alleging emotional harm from data breaches or privacy violations must now choose between two distinct procedural avenues, depending on the nature of their injury:

- Psychiatric Injury Track:

Where a data breach results in a medically recognised psychiatric condition — such as depression, PTSD or anxiety disorder — the case is treated as a personal injury action and requires IRB authorisation. - Emotional Distress Track:

Where the plaintiff claims non-clinical distress, such as inconvenience, worry, or temporary anxiety, the claim does not fall under the IRB regime. These actions may be pursued directly in court without prior authorisation.

The judgment acknowledged the trade-off between the two tracks. The IRB system is more cost-effective and efficient but offers less flexibility than litigation before the courts. We previously published an article on How Irish Courts Are Handling Data Breach and GDPR Claims. Time will tell which route now becomes more common, particularly in data protection and consumer claims.

The Limits of Negligence for Emotional Distress

The Court also clarified that where emotional harm falls short of psychiatric injury, negligence is not a viable cause of action. This is because emotional upset alone does not meet the “damage” element required to sustain a tort claim in negligence.

As Murray J noted, Irish law has long distinguished between recognised injury and non-actionable emotional disturbance. While emotional distress may sometimes be compensable in contract or under statute (such as the Data Protection Act 2018), it does not transform into a personal injury for other legal purposes.

The Role of GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018 for Data Protection Litigation in Ireland

Mr Dillon had also brought his claim under section 117 of the Data Protection Act 2018, mirroring Article 82(1) of the GDPR, which allows for compensation for both material and non-material damage.

While this legislative framework supports recovery for distress caused by data breaches, the Court confirmed that such claims do not become personal injury claims unless psychiatric injury is present. This distinction preserves access to redress under data protection law without triggering the procedural requirements of IRB.

A Warning on Pleading and Procedure

One of the most important procedural lessons from the case was the emphasis placed by the Court on accurate pleading. Murray J stated repeatedly that it is the responsibility of the plaintiff — not the courts or defendants — to clearly state:

- The type of harm for which compensation is sought, and

- The legal basis of the claim (tort, statute, contract, etc.).

Mislabelled claims, or those that blur the boundaries between personal injury and non-injury proceedings, may be vulnerable to procedural objections — or worse, outright dismissal.

Solicitors are now on clear notice that claims involving emotional distress should only proceed through IRB where there is evidence of psychiatric diagnosis. Otherwise, they must be pleaded accordingly and initiated through the ordinary civil courts.

What Can Insurers and Data Controllers Learn

This Supreme Court decision provides much-needed clarity for claimants, insurers, and legal practitioners:

- Emotional upset claims without psychiatric evidence can now proceed outside the IRB regime.

- IRB authorisation is only required for personal injuries supported by medical or psychiatric diagnosis.

- Negligence claims for emotional harm alone are likely to fail, as they lack the injury element.

- GDPR/data breach litigation can proceed in court for non-material harm, but awards are likely to be modest without clinical injury.

- Solicitors must ensure claims are accurately pleaded and the correct procedural route is followed.

Final Thoughts from Lacey Solicitors

The judgment in Dillon v Irish Life marks a another turning point in Irish litigation. It draws a firm procedural and legal boundary between actionable personal injury and general emotional harm — offering clarity where confusion had prevailed.

At Lacey Solicitors, we act for both claimants and insurers in personal injury, insurance disputes, and data protection litigation across Dublin, Belfast and beyond. Whether you’re seeking to initiate proceedings or responding to a claim involving a data breach, our experienced litigation team can advise on the correct legal framework and best course of action. Use our Online Portal to speak with a member of our team.